493

One of the interesting things about studying local history is coming across the variety of unique and distinguished people who made their home in our community during part of their lives.

One of the subjects of this column is a gentleman I had ne

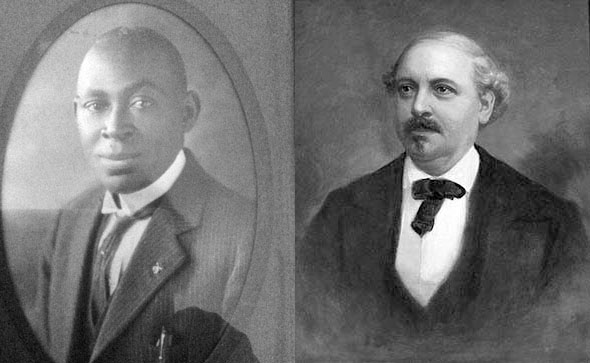

Introducing two historical legacies of the legal profession

previous post