Opponents of keeping the contained burn chamber at Camp Minden are questioning the stack emissions test results from the pollution abatement system.

Dr. Brian Salvatore, Camp Minden Citizen Advisory Group member, said while the Environmental Protection Agency and the contractor, Explosive Service International, are testing for whole hydrocarbons, the results for the components of the gas are not what they appear to be.

“There are emissions that are not being properly counted on how harmful they can be, such as aromatic hydrocarbons,” he said, “Things that can cause cancer, and we’re not distinguishing those in our sensing technology from things that are produced by our pine forests and things that may be in our gasoline that are not cancer-causing. Yet we know that there’s probably 150 pounds of stuff coming out of the system and we don’t know what it is. We know that they’re hydrocarbons.”

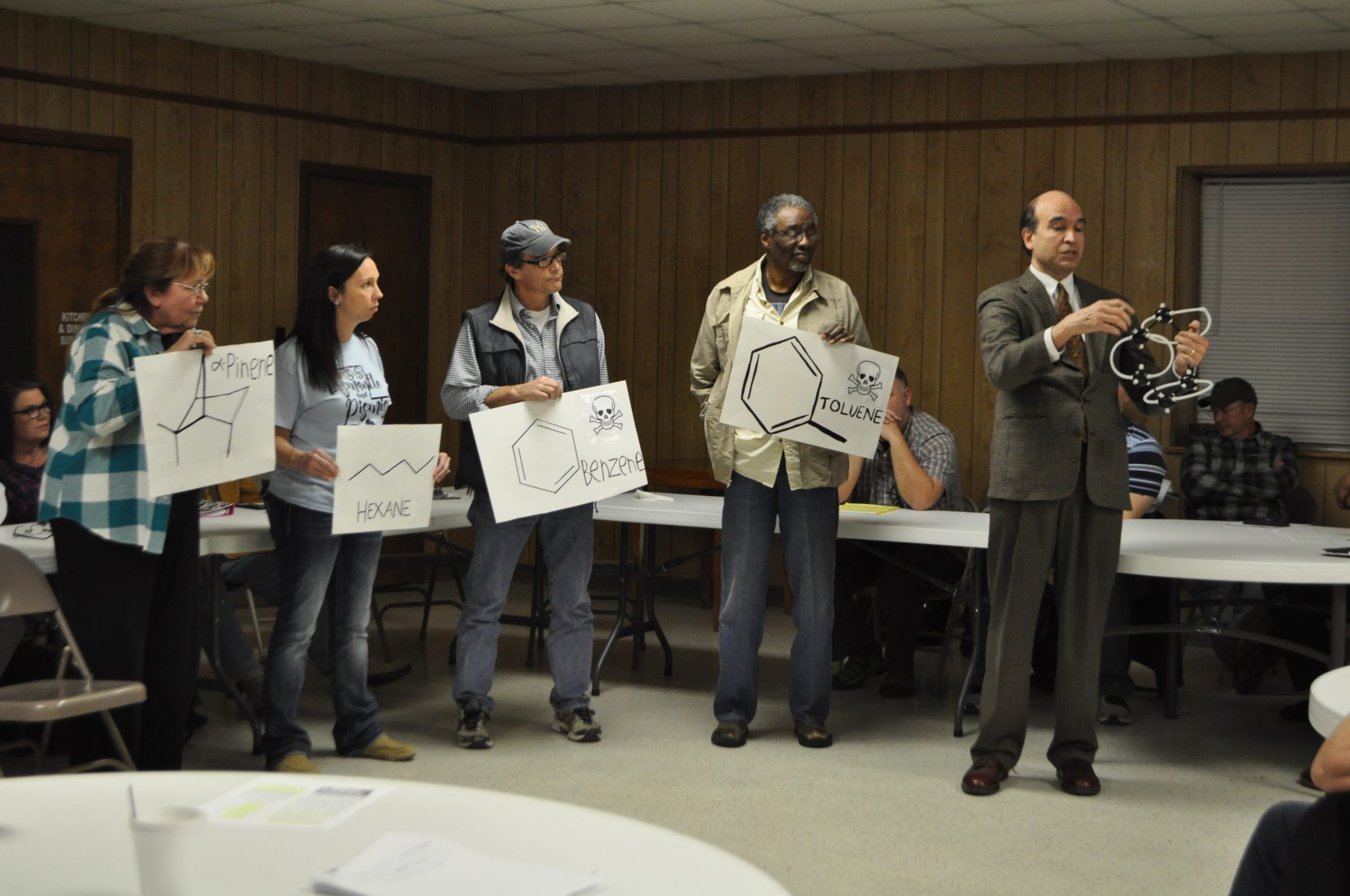

He said the problem is the total hydrocarbons he discussed during a presentation at a CAG meeting Monday are not being distinguished between the harmful ones, such as benzene and toluene, and the non-harmful ones, such as pinene and hexane.

“Right now, when they’re telling us there’s no emissions, which is false, they’re not even promoting to test anything if they’re saying there’s zero emissions,” he said. “All we know is that we have a combination of something harmful and something not harmful. None of them are good for you. The pinene is not so bad and the hexane in small amounts is not so bad. But benzene in small amounts – one part per billion – is documented to raise the cancer rates if you breathe it every day.”

ESI Vice President Jason Poe countered Salvatore, saying the stack emissions have been tested three times by two independent companies. Metco was hired by El Dorado Engineering, and Weston Solutions was hired by the EPA. Test results from the comprehensive performance test in April, and tests again in July and October 2016 have been published.

“He can’t knock the emissions data,” Poe said. “Now they’re going after the data that the EPA and DEQ have approved and been vetted by a third party contractor three times now. We’ve done initial start up and two stack tests. They’re all basically the same result – non-detect. We’re putting out lower emissions than we’re contracted to do.”

Dean Schellhase, project manager for the M6 disposal, explained what they test for quarterly. He said they test for the principal hydrocarbons in M6 “neat” propellant – dinitrotoluene (10 percent by weight), dibutylpthalate (3 percent by weight), and diphenyldiphenylamine (1 percent by weight), the stabilizing agent for the propellant.

“We monitor continuously for oxygen percent, carbon monoxide, nitric oxides and total hydrocarbons,” he said.

The 21-day report from January, published on ESI’s dashboard at www.esicampminden.com, show where the volatiles, semi-volatiles and total hydrocarbons were tested. It also included test results for hexane, benzene and toluene.

“The comprehensive performance stack emissions test sampled over eight days for all volatile and semi-volatile organic compounds to include the three ‘d’s,’” Schellhase said. “They also sampled for heavy metals. Nothing was detected. Every three months, we conduct a similar test for the volatiles and semi-volatiles. State and federal regulations require continuous monitoring of either carbon monoxide or THC to demonstrate compliance of the process. We monitor both and report the carbon monoxide to demonstrate compliance. THCs go out in the 21-day reports.”

During his presentation, Salvatore explained some of the different volatiles and semi-volatiles that make up total hydrocarbons. Hexane is found in gasoline. Pinene is released by pine trees, he said. These are not carcinogens. Benzene and toluene are cancer-causing chemicals, he said.

He said he felt everyone was in a hurry to get rid of the CBI and M6, and in the process, some things slipped through the cracks. He said the dialogue committee asked for the sensors that would detect all the chemicals that make up total hydrocarbons, but due to the urgency of the project, they didn’t get them all.

“If they did it because they were in a hurry, I understand,” he said. “Now they are done with the process, they should see they should have thought this through better. If they’re ever going to install this system again, they need better sensing technology than they put on ours. We have a very good system, and it operates like a good incinerator. But a very good incinerator still has emissions. One hundred pounds per day of organic hydrocarbons, it’s not something we should say we don’t have any concern about.”

Salvatore said 425 million liters of air is going through the system per day.

“What’s the consequence of that? Dilution. If there’s anything that’s really, really bad, it’s diluted and it will look like it’s got a low concentration,” Salvatore said. “That’s my concern. I can’t tell you that, because we don’t have the sensors. But based on what I know of chemistry, these are the guys (benzene and toluene) that are going to survive if you have total hydrocarbons content.”

As of Wednesday, about 13 million pounds, or 82.2 percent of the M6 has been destroyed.